When I was 11 years old, I visited cousins in Downer’s Grove, a Chicago suburb, and they took me to the Chicago Institute of Art. I had never been to an art museum before, and I was thrilled. Back at the ranch, my mother subscribed to a series of art books from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and every month or two a new volume would arrive and we would pore over the 8×10 cut sheets from the envelope inside the back cover. But to see some of these works in person—Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World, Monet’s Haystacks, Grant Wood’s American Gothic —took my breath away.

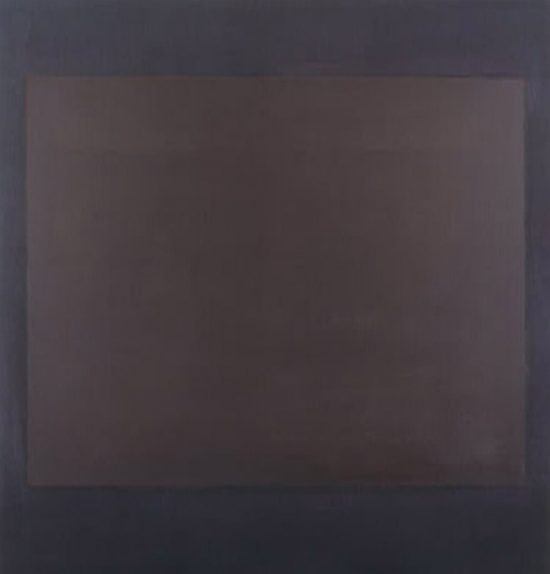

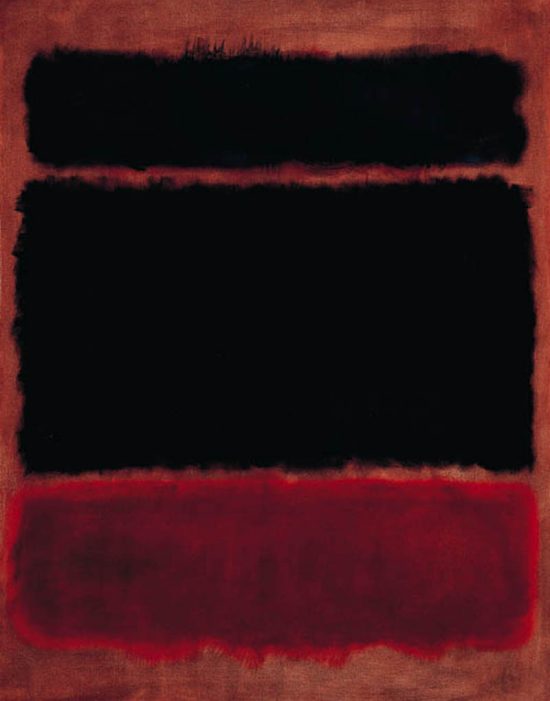

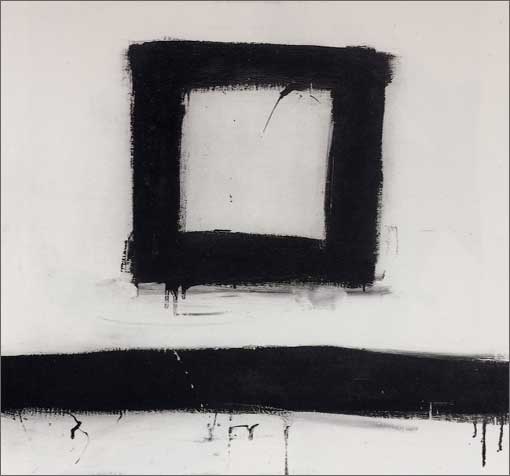

But then I entered a room where a massive black-on-black painting took up an entire wall. I had never heard of Rothko; if there were any reproductions of his work in the Metropolitan series, I had missed them or that volume hadn’t arrived yet. And though I considered my college-educated parents sophisticated—not many ranchers subscribed to art books—they were very much of the school that if you couldn’t recognize what was being portrayed, it wasn’t art. This was just the sort of painting that they would have ridiculed: a 5-year-old could have painted it.

But then I entered a room where a massive black-on-black painting took up an entire wall. I had never heard of Rothko; if there were any reproductions of his work in the Metropolitan series, I had missed them or that volume hadn’t arrived yet. And though I considered my college-educated parents sophisticated—not many ranchers subscribed to art books—they were very much of the school that if you couldn’t recognize what was being portrayed, it wasn’t art. This was just the sort of painting that they would have ridiculed: a 5-year-old could have painted it.

My cousins had let me wander on my own or perhaps I had just slipped away, but by the time I reached this gallery, I was unaccompanied. After my initial dismissal of the silly painting, I didn’t walk away. Instead, I saw down on a bench facing it. I don’t know why; perhaps I was tired. But I started to look at it, really look at it. The more I gazed, the more deeply it seemed to recede. I had a distinct impression of being transported inside it. It was like walking around in a great dark forest but I didn’t feel lost or afraid. Instead, I felt comfort and space. I didn’t have words like transcendent or transporting in my vocabulary, at least not in relation to art, but that was what I experienced.

As with my early exposure to Franz Marc, I didn’t look into Rothko until decades later. When I did, I learned that he intended his paintings to have exactly the effect that I had experienced. Rothko wanted his viewer to feel, in his words, “enveloped within” these works. When he was accused of using scale to divert attention from a lack of content, he responded:

I realize that historically the function of painting large pictures is painting something very grandiose and pompous. The reason I paint them, however . . . is precisely because I want to be very intimate and human. To paint a small picture is to place yourself outside your experience, to look upon an experience as a stereopticon view or with a reducing glass. However you paint the larger picture, you are in it. It isn’t something you command!

According to Wikipedia (that source of all sources), he “even went so far as to recommend that viewers position themselves as little as eighteen inches away from the canvas so that they might experience a sense of intimacy, as well as awe, a transcendence of the individual, and a sense of the unknown.” He communicated this so well that I experienced it, even as an eleven-year-old girl from the high plains of Wyoming on her first-ever trip to the city. It changed my expectations for art forever.

By the time Rothko evolved into the color field paintings that he is most known for, he had been painting for over 30 years. His early figurative work in the 1920s and 30s showed the clear influence Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso, Milton Avery and others. In the 1940s, reading Freud and Jung and Nietzsche, be began to draw heavily on imagery and myth, in part as a response to the increasing tensions around the world that led to WWII. By the time the decade ended, he had moved entirely into abstraction. (The National Gallery of Art website offers an excellent overview that shows the progression of his work.)

By the time Rothko evolved into the color field paintings that he is most known for, he had been painting for over 30 years. His early figurative work in the 1920s and 30s showed the clear influence Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso, Milton Avery and others. In the 1940s, reading Freud and Jung and Nietzsche, be began to draw heavily on imagery and myth, in part as a response to the increasing tensions around the world that led to WWII. By the time the decade ended, he had moved entirely into abstraction. (The National Gallery of Art website offers an excellent overview that shows the progression of his work.)

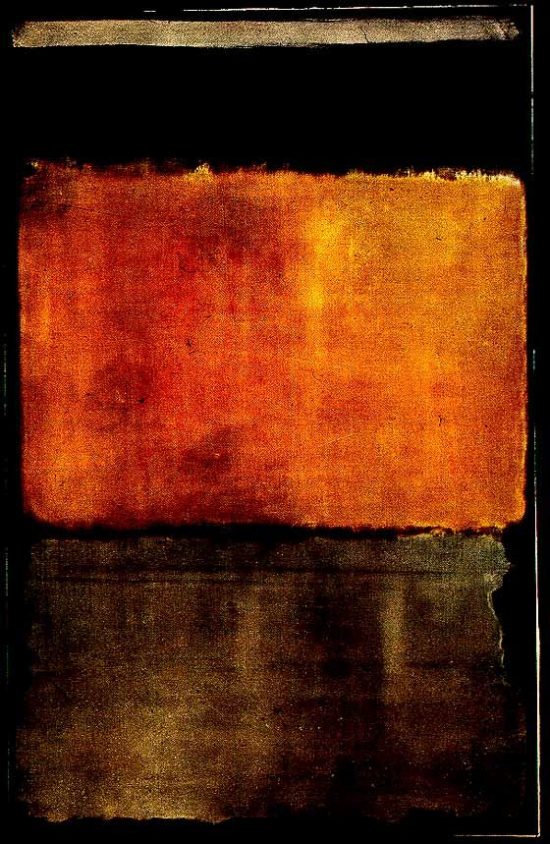

Rothko wrote prolifically, and he was clear about the spiritual intentions behind his work. He believed that a primary role of the artist was to be a myth maker and wrote that “the exhilarated tragic experience is for me the only source of art.” He knew something of tragedy: his Jewish family had fled Russia before World War I; he lost family members in the holocaust in World War II. In time, he rejected being classified as an abstract painter as he had earlier rejected being called a colorist, writing that he was interested

…only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on. And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions… The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationship, then you miss the point.

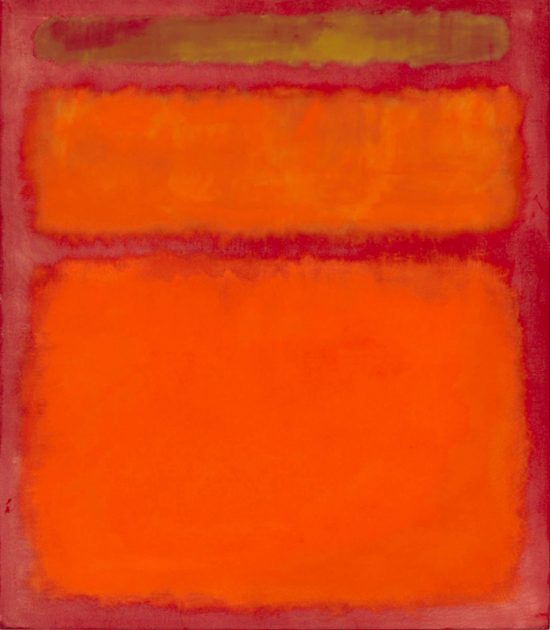

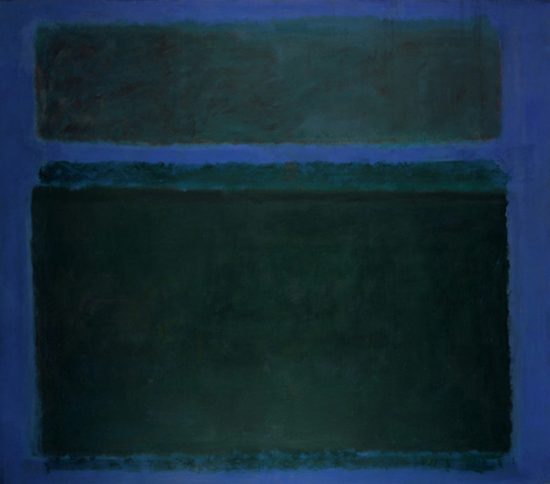

What speaks to me most profoundly in the color field paintings:

The spiritual resonance: The spirituality of these paintings is something that can’t be put into words. They are spaces, cathedrals. The art critic Jonathan Briggs at Harvard speaks of the “omnivalence” of a great work of art, that quality that is more than any one thing: sacred and profane, simple and complex, flat and spacious. You can’t get to the bottom of these paintings except to know that they come from complete engagement and great attention.

Color: Well, obviously. But the vibration of one color against another, the depth of layers of color in slight variations, the proportion of one color in relation to another—all are formal factors that combine to create an emotional engagement.

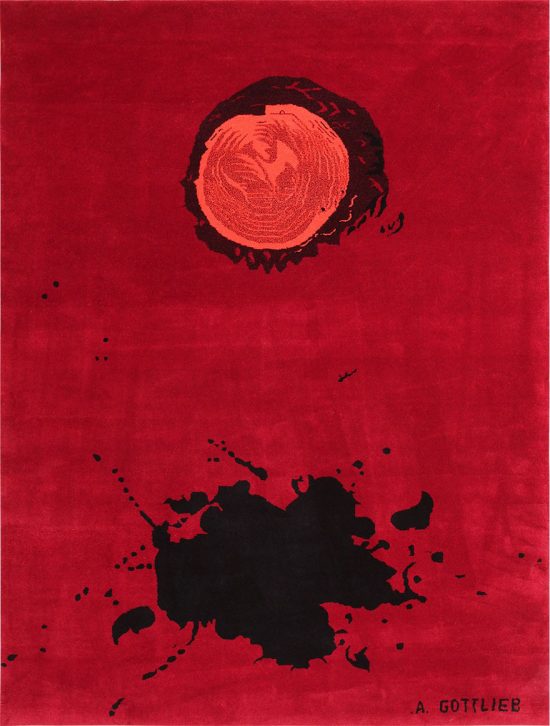

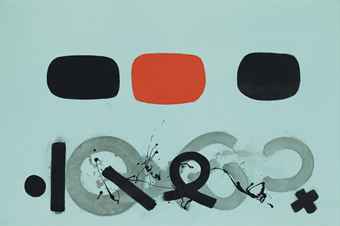

Depth: In a manifesto Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb wrote for a show they had together in 1942, they stated that ” We wish to reassert the picture plane. We are for flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.” And yet Rothko’s color fields are anything but flat. This great contradiction is part of the power of omnivalence in his work. And it’s a contradiction that intrigues me in my own affinities. I love three-dimensional form rendered on a two-dimensional surface. It is an alchemy that never ceases to intrigue me. I will write later about my love of sculptors’ draftsmanship, as in Henry Moore’s sheep sketchbook. But I also love Diebenkorn’s flat, abstracted landscapes. Somehow, Rothko combines both. He wanted the viewer to walk around in his spaces, and I do.

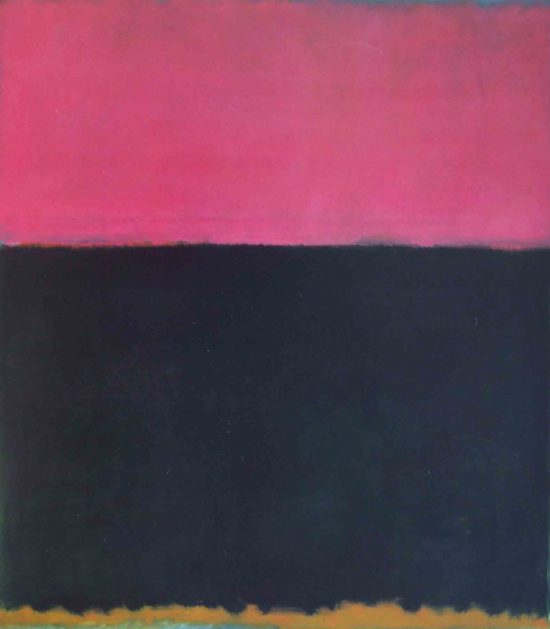

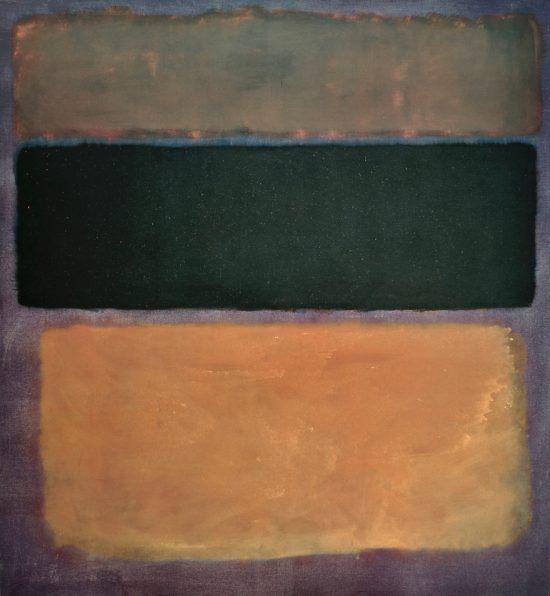

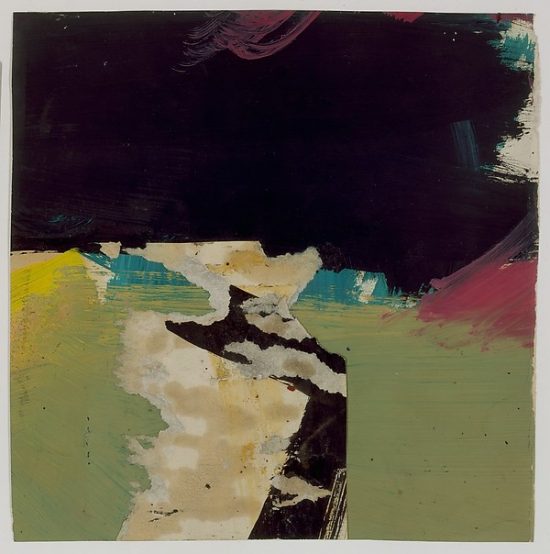

Some more of his work:

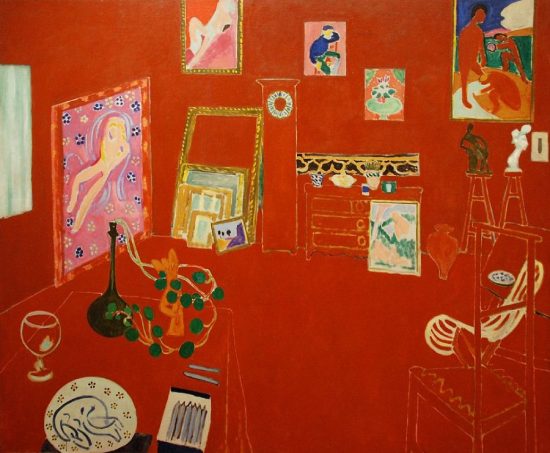

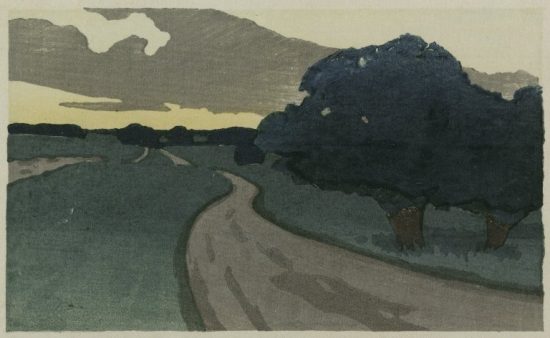

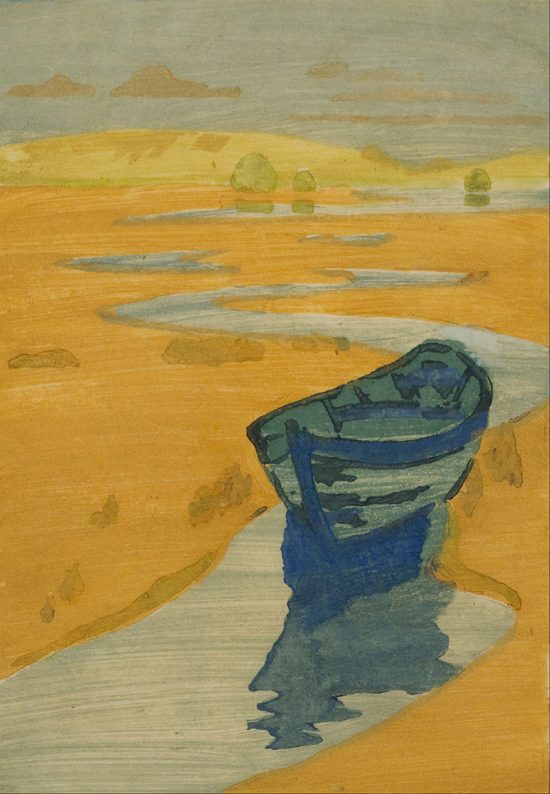

Some of his influences:

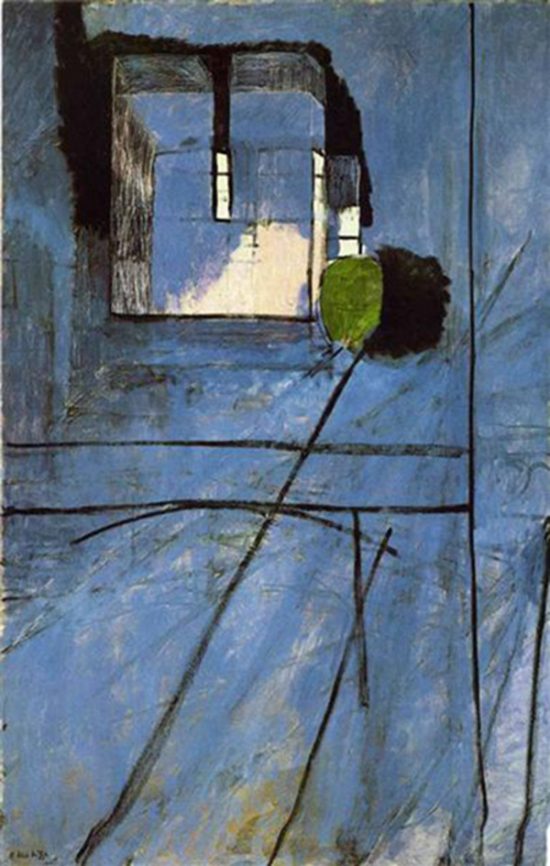

Henri Matisse, 1969-1954, especially his use of dominant color in The Red Studio and color form, especially black, in the Window at Coullioure. Mattie had written “I began to use pure black as a color of light and not as a color of darkness,” a thought that surely inflected Rothko’s darkening palette in his later years.

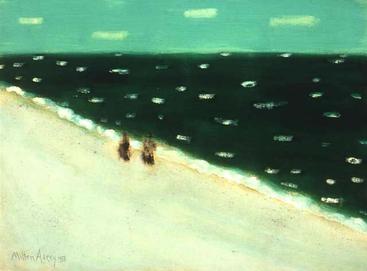

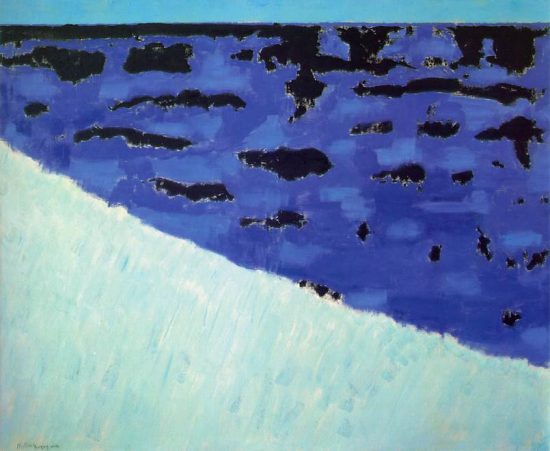

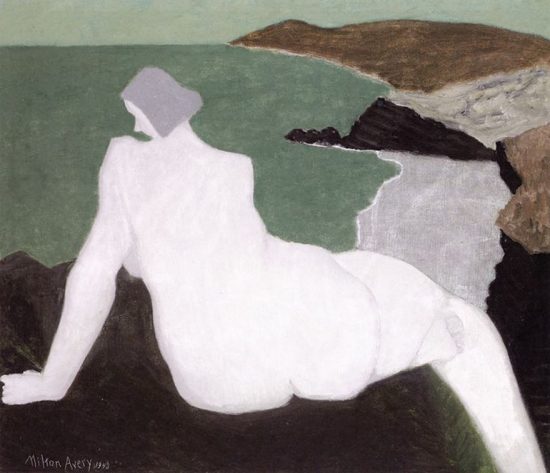

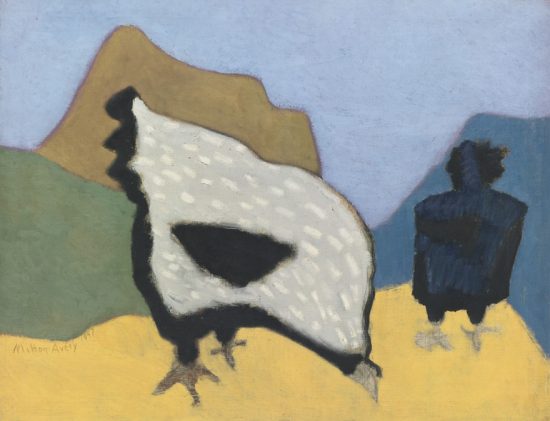

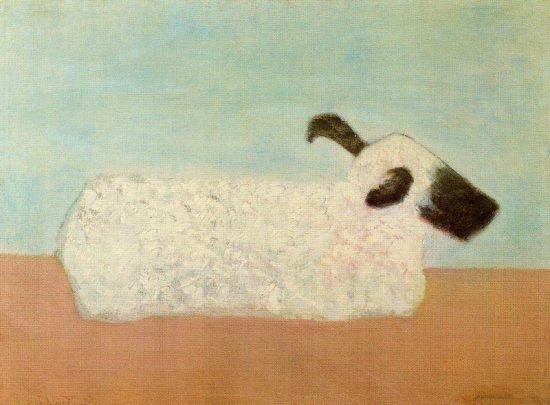

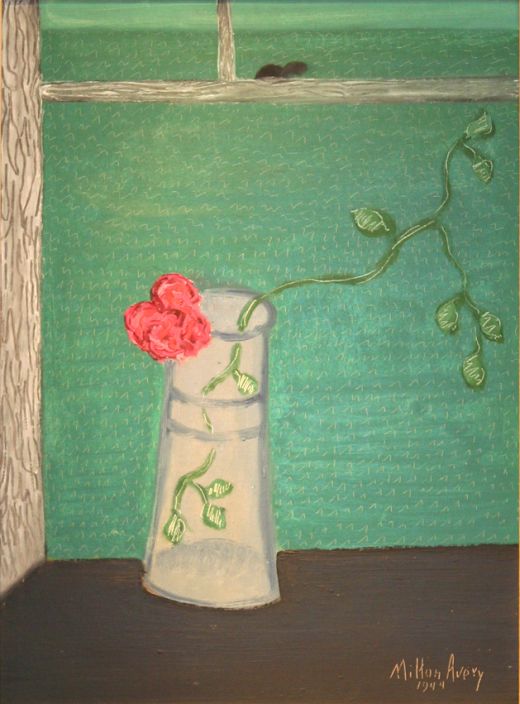

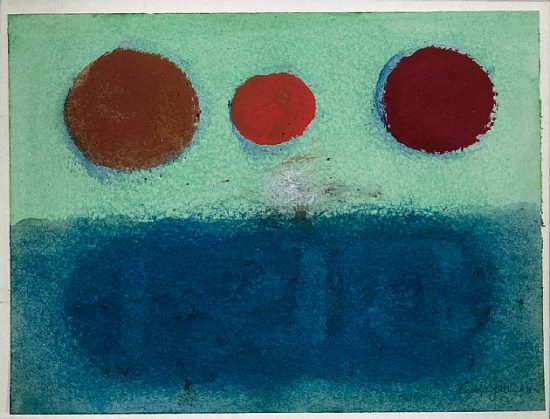

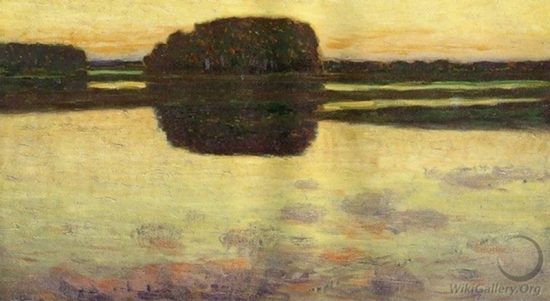

Milton Avery, 1885-1965, one of Rothko’s teachers, once said, “”I try to construct a picture in which shapes, spaces, colors, form a set of unique relationships, independent of any subject matter. At the same time I try to capture and translate the excitement and emotion aroused in me by the impact with the original idea.” His large flat forms and use of color influenced Rothko. I was surprised to find Avery occasionally worked with some of my favorite subjects: cows, sheep, chickens. I’m not especially fond of his cows and sheep (the texture on the sheep seems so uncharacteristic of Avery; perhaps it was early), but his chickens knock me out. And I love his figures.

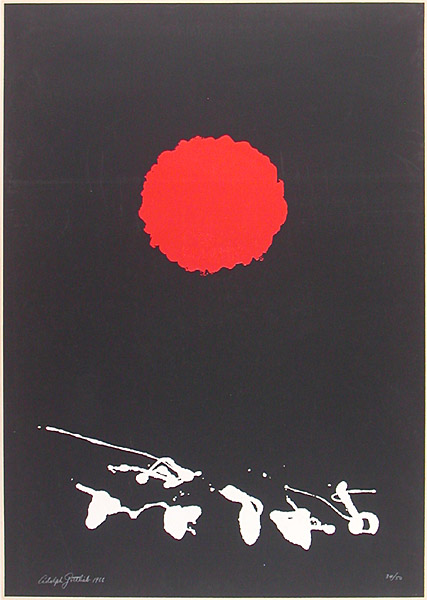

Adolph Gottlieb, 1903 – 1974

In 1947, Gottlieb’s words from 1947 ring oddly prescient today:

“The role of artist has always been that of image-maker. Different times require different images. Today, when our aspirations have been reduced to a desperate attempt to escape from evil, and times are out of joint, our obsessive, subterranean and pictographic images are the expression of the neurosis which is our reality. To my mind certain so-called abstraction is not abstraction at all. On the contrary, it is the realism of our time”.

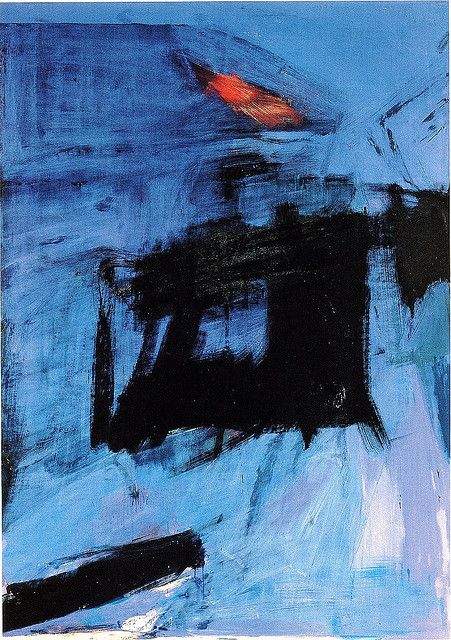

Franz Kline, 1910-1962

Kline was known as an action painter and his bold calligraphic works seemed utterly spontaneous but he actually worked them up over time. He would start by creating innumerable fast gestures on pages of old telephone books and then choosing from these images that he wanted to work into large canvases.

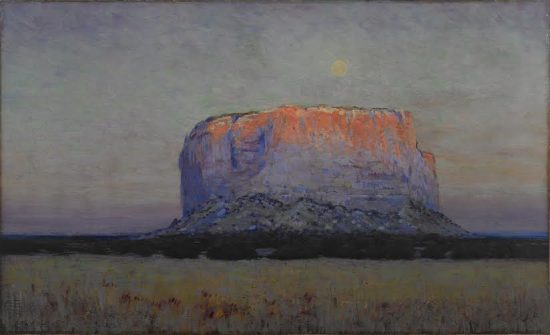

Arthur Wesley Dow (1857-1922)

“His ideas were quite revolutionary for the period; he taught that rather than copying nature, art should be created by elements of the composition, like line, mass and color.[2] He wanted leaders of the public to see art is a living force in everyday life for all, not a sort of traditional ornament for the few. Dow suggested this lack of interest would improve if the way art was presented would permit self-expression and include personal experience in creating art.” (Wikipedia)

No comments yet.