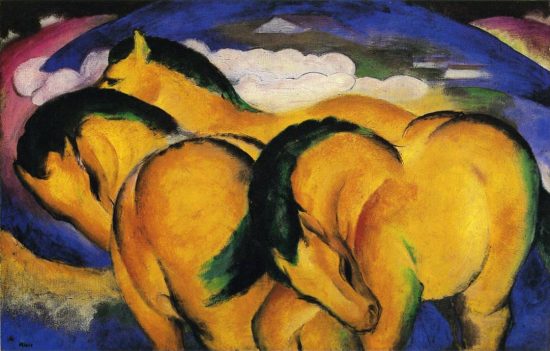

I believe that I am an artist, at least in part, because of a print that hung over the love seat in the isolated Wyoming ranch house were I grew up. All the other art in the house was Western, reproductions of works by Charlie Russell, Frederic Remington, and Will James. “The Red Horses” by Franz Marc was the single exception, something my mother had brought back from Germany after my father’s service there in the post-war occupation.

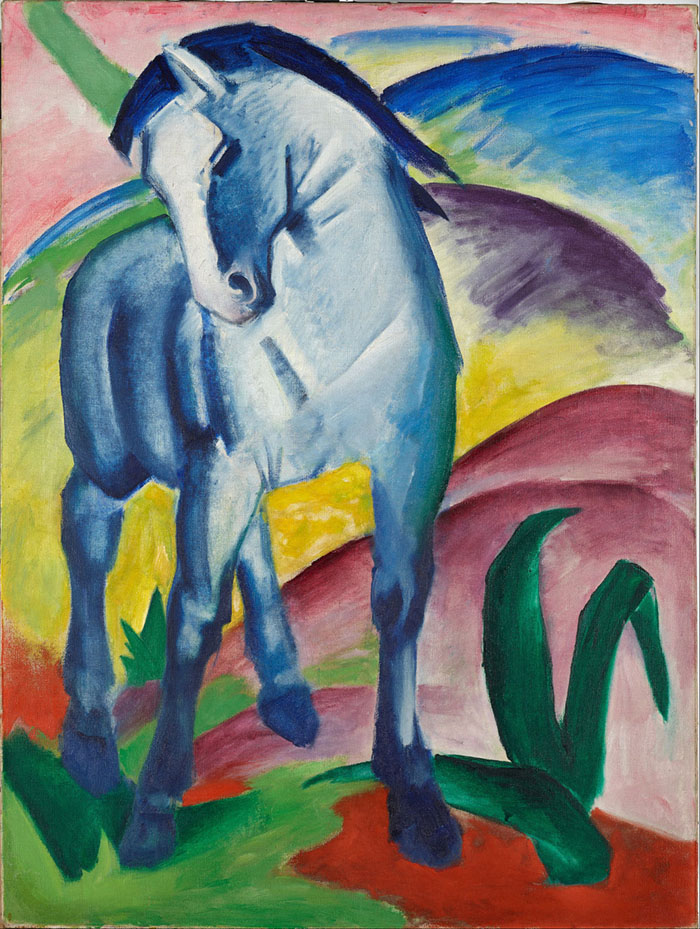

I could look at it for hours: three horses, luminous with shades of crimson, vermillion and orange; one in motion, another grazing by a craggy, cobalt ledge, and the third looking away from the viewer, off into infinite distance. The horses were not ‘real,’ the colors were not ‘real,’ even the landscape was not ‘real.’ Yet Marc had captured something that more strongly resonated with my own experience than the hard-muscled accuracy of Russell and the rest. Years later, I would learn that Marc, co-founder with Kandinsky of the Blue Rider group in Germany, turned to animal subjects in his quest for spiritual purity; all I knew at the time — and this was a felt knowledge rather than an articulated one — was that his painting spoke to me. I was said to have a slight gift with horses; the extent to which this was true, I realize now, had much to do with a sensibility I could not have described but found manifest in Marc’s work.

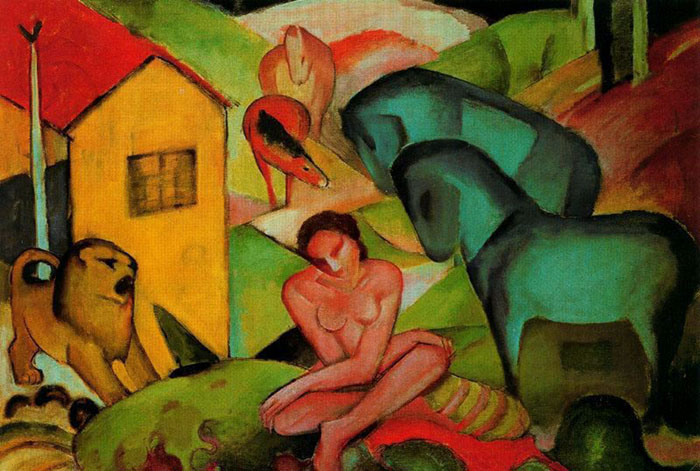

Marc was born in 1880 in Munich and died in the battle of Verdun in 1916, at the age of 36. The subjects of almost all his work were animals, and his depictions of them changed as the world descended into the chaos of World War I during his short life. His earlier work was infused with a sense of harmony and spirituality; later, it became more cubist and shattered.

The Fate of the Animals is perhaps the most well known of his dystopic work: it contains no horizontals or vertical oritentations, only diagonals. The animals are panicked and contorted. On the back he wrote “Und alles Sein ist flamed Leid”: “And all being is flaming suffering.”

In the center of the painting stands a blue deer, interpreted as a symbol of hope, shying away from a falling tree. As one critic put it,

That Marc chose to place this symbol of hope in the center foreground of the composition, suggests that he himself had a hopeful vision of the future. What’s more, the fact that Marc borrowed from the Futurists in his painting style suggests that he had a positive view of the destruction he depicted. Since destruction was a necessary step before society could be rebuilt, this powerful image could be read as not only tragedy and decimation, but as progress.

But if Marc once thought that war would purify the world, he was soon disillusioned. In 1915, he wrote about the painting in a letter to his wife from the front: “[It] is like a premonition of this war—horrible and shattering. I can hardly conceive that I painted it.”

I knew nothing of this when I gazed at The Red Horses as a child. I didn’t even know the artist’s name. My mother died when I was 20; the ranch was sold a year later; I don’t know what happened to the print. I never forgot about it, but it receded from concern. In my thirties, I began to wonder what it was titled and who had painted it, and when I traced it to Franz Marc, I began to look at Marc’s other works. The harmony and fullness of his early work speaks to the deepest part of me, that child who lived around few other children but was surrounded by animals and found great nurture there. And his dystopian works speaks to a fear of chaos that has haunted me all my life (more about that later, as I write about aversions.)

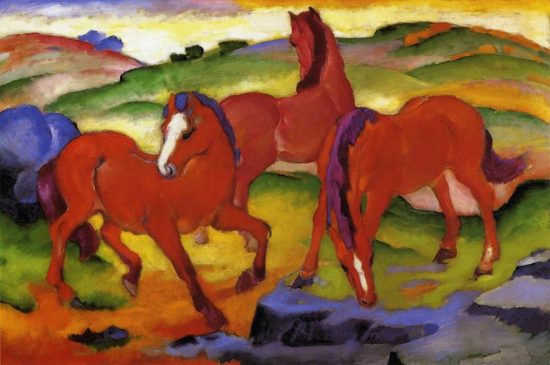

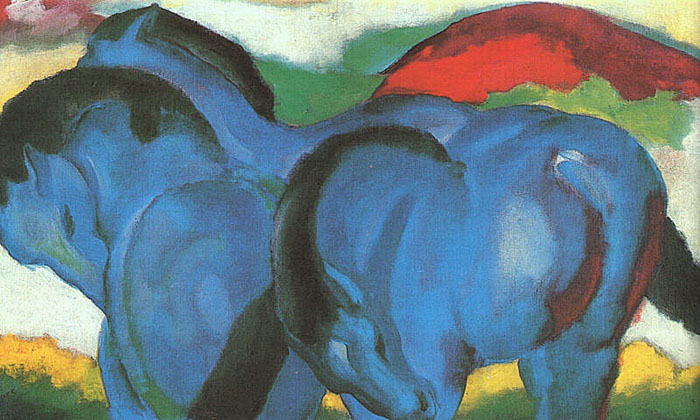

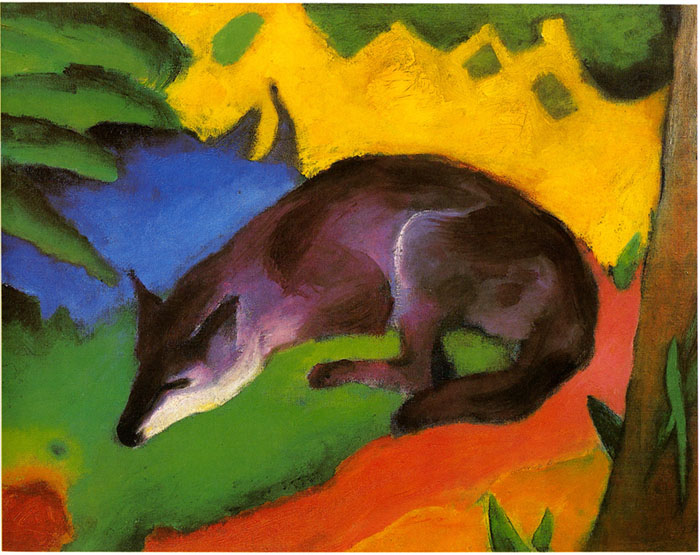

These are the things that speak to me most profoundly in his earlier work:

The weight and corporeal gravity of his figures. I was one of those anxious kids who felt like she was adopted; I never felt like I quite belonged. This, coupled with the fact that we lived so far out in the country and in such isolation—the one room school I attended had only four or five other students at any one time—made me much more comfortable with animals that with people. I yearned for the sense of comfort they had in their own bodies, and with how they inhabited the world without questioning whether they had a right to be there. We had two dogs and two cats in the house; I rode horses daily from long before I could remember. I have been physically connected to animals my entire life and the warmth and bulk of animal bodies is, to this day, a great comforts. Marc’s earlier figures embody a sense of belonging that resonates at a deep emotional level for me.

Color: For Marc, Kandinsky, Klee, and others of the Blue Rider school, color had spiritual significance. I have read that blue was masculinity and spirituality, yellow was feminine joy, and red symbolized the sound of violence. I don’t get a sense of violence through Marc’s use of red in his earlier works; rather it seems more like passion or eros. But the balance of his colors, their vibrance, both please and move me. And though I know they were chosen for specific purpose, they have a rightness to them.

Composition: In his earlier paintings, the large forms filling the picture plane give a sense of solidity, of “thereness” or deep engagement. Conversely, the later compositions are busier and and more fractured, filled with as palpable a sense of anxiety and fear as the earlier ones were with a sense of serenity and wholeness. In art in general, I am repeatedly drawn to large forms and simple compositions, wanting to inhabit that more harmonious, grounded world. And tracing Marc’s work as the world disintegrated around him–and ultimately led to his violent death—gives me insight into my own fears.

Some more from Franz Marc:

No comments yet.