I have followed the work of Deborah Butterfield for thirty years and it never fails to reduce me to tears. It also leaves me in a puddle of the most pure and absolute desire. If I was allowed only one art book to last me the rest of my life on that proverbial desert island, it would feature the work of Deborah Butterfield. If Christie’s Auction House gave me a blank check, I would buy something by Deborah Butterfield. If only, if only, I could live with one of her horses.

As I have launched on this project of looking into the art that most inspires me, certain characteristics keep coming to the fore. One is gravity or mass. Another is strength and confidence in the form, something that might be called essential or true. I respond to the beauty of line; to color, which may be bright or monochromatic as long as it carries a sense I can only describe as vibrant harmony. Another huge factor is emotional content–manifested through a quality of deep and many layered resonance that the critic Jonathan Briggs calls omnivalence. Ambivalence is “maybe this or maybe that.” Omnivalence is “this and that.” The Mona Lisa is innocent and wicked, sacred and profane, wistful and content, seasoned and childlike. These horses of Butterfield’s are strong and vulnerable; peaceful and wary; solid and porous, flesh and blood and industrial detritus.

As I dig into the biographies of artists I admire, I am intrigued to find that almost all of then have a spiritual yearning at the core of their work, a desire to experience oneness or transcend the barrier between self and other or artist and artwork or what is described and what is actually experienced. Obata approached this through the zen concept of kiin seido; for the German Expressionists it was Einführung or empathy; Rothko wrote about the “exhilarated tragic experience” that was the source of all his work. The American Art Museum suggested that Butterfield has referred to the “spiritual expression of the horse as a metaphor of human experience,” but I wonder if this is not something of a misquote. Her horses are so powerful, so spiritually charged, not because of what they say about us but for what they say about themselves.

In her essay for the 2003 book Deborah Butterfield by Robert Gordon, the Pulitzer Prize winning author Jane Smiley wrote about the “absolute horsiness” Butterfield is able to capture:

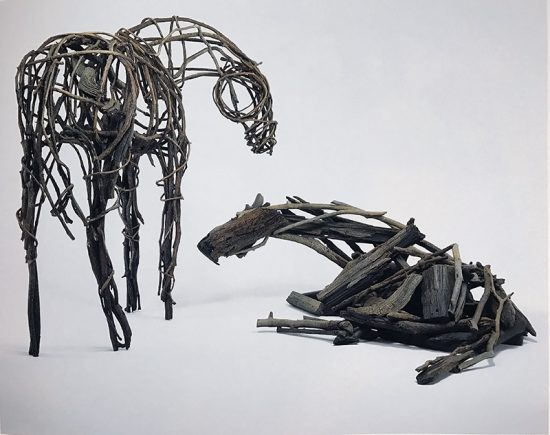

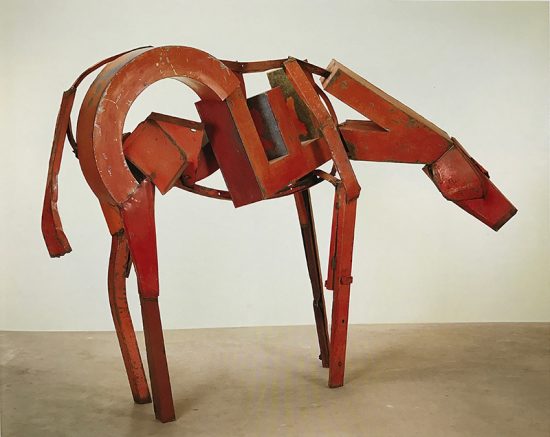

…as peaceful as if they were standing alone in a field, out of the human gaze… I have never met a horse lover who did not gasp at the truth of Butterfield’s horses, and then again at the paradox that they are made of such industrial materials, barbed wire, bronze, pieces of junked cars, discarded metal letters…. Whatever they mean, however she intended them, however they fit into contemporary art or women’s art or even into Butterfield’s life, first and foremost, they are extraordinarily right.

Smiley points out that Butterfield’s work established “an entirely new form of equine art” in that her horses are not objects for the glorification of the rider or cultural triumphalism, as in equestrian statuary and so much art of the court, the hunt, and the American West. Butterfield’s horses “ask us to look at them for themselves, not for what they do for humans. [They] are not useful animals in the traditional sense…. They are themselves—they have names and all have individual natures, expressing feelings of their own…. All of Butterfield’s horses, even the most quietly statuesque, seem to have inner lives.”

Contemporary art criticism makes much of “the gaze”; if much artistic rendering of the female form derives from the male gaze, much art of the horse is a way for men and women to gaze back at themselves in ways they want to be seen: courageous or triumphant or athletic or as an accomplished equestrienne, in harmony with her mount. In each of these cases, it is much more about the rider than the horse. Another irony—and omnivalence—in Butterfield’s art is that she depicts horses beyond the human gaze … and by her depiction lets us gaze at them without interruption.

As I try to put this into words, I realize that this is a quality that draws me to the work of Butterfield and my other important influences. I can stand in front of a Rothko or a work by Franz Mark and enter into it without feeling like an intruder, an interloper. The veil between me and the work can seem to disappear and in that moment I am at home not only in the work but in my own body and in the world; I have ceased to be a trespasser: other, outside.

If I suspect that Butterfield was misrepresented as suggesting that she used the horse primarily as a metaphor for human spirituality (rather than being drawn by the horse’s inherent spirituality on its own terms), I have no doubt that she finds spirituality in her work, both in her relationship with the horses themselves (she spends several hours a day practicing dressage) and in her choice of materials with which to represent them. “I have been collecting driftwood and assorted debris all my life, finding beauty and order in the disorder and disintegration of our treasured or discarded everyday objects,” she said in speaking about her exhibit at the Greg Kucera gallery in Seattle in 2016, noting that she liked to use “emotionally, spiritually and tragically infused material.”

One of the things that intrigues me about Butterfield’s work is how 30 years ago she found her artistic soul, a “truth” in working that has sustained her ever since. She used stick and mud in her early horses. Wanting more durable material, she started using found metal around 1979 and started casting wood constructions in bronze not long after. If I compare Palomino from 1981 with Paint and Henry five years later, I can see that she was quickly learning to do more with less. But it takes a more practiced eye than mine to sense a greater “essence” in later work than in what was manifest in Paint and Henry three decades ago. And yet there is no sense of her work being redundant or stagnant or tired. Just as there is no redundancy between one living horse and another—or between any living spirit and another—each piece (or at least the successful pieces that make it into exhibition) carries a truth, an “essentialness.”

Smiley wrote about a moment of recognition for Butterfield in the development of her art:

It was the Vietnam War that convinced her to try horses. Detesting the link between horses and war that seemed universal, she decided to create mares who were not warhorses—mares made out of plaster, paper mâché, and mud, made out of mud and sticks and sticks. One of her first installations was a group of six mares in a room, all looking toward the door. The visitor had to brave the gaze of the life-size, mottled brown and white animals and then squeeze among them once inside. Lots of viewers looked in, but declined to enter, even though the mares’ ears were pricked and their demeanor calm. That was when Butterfield began to realize the power of her subject and her vision of it.

I yearn for this clarity of vision, this recognition of a personal visual language and subject matter. With your help, I hope to recognize it. And then I’ll pray for the strength and stamina to develop it.

I want to end this rumination with another quotation from Jane Smiley. So often I find that the most compelling writing about art is not by trained critics or art historians but by articulate devotees who are not formally trained, and of all the writing I have read about Butterfield, Jane Smiley’s seems most on the mark. My last post on Obata got me thinking about the interplay of the masculine and feminine in my own aesthetic affections, and Smiley addresses its role in Butterfield’s work in the conclusion of her essay:

When I look at her horses, I see something important that perhaps Butterfield is too modest to acknowledge—if there is a feminine strength and receptiveness to her horse sculptures that are made of old steel letters and car fenders and rebar and pieces of signs and barbed wire and other detritus of industry, it is Butterfield who has put it there. If crooked sticks and thorns and pieces of fencing and pieces of driftwood have been bent and brought to order, it is Butterfield who has accomplished it. To my mind, she has done a particular, honorable thing that often falls to women—she has cleaned up the ugly messes that others have left behind, she has found beauty in the discarded and revealed it. Is this an artistic vision? You bet it is, because it is a valid and necessary response to one of the identifying features of our era—the realization that we have nearly destroyed the world we live in, along with it the natural part of ourselves, and are still in danger of doing so. Butterfield’s work is a generation beyond the work of painters and sculptors of the postwar period, who chronicled the breakdown of human perception into bits and pieces and jagged fragments. In her own jagged fragments, Butterfield finds humankind’s most reliable and yet mysterious natural ally, horses. Horses are figures and the landscape, the connection between ourselves and the natural world.

Her horses are, after all, about reintegration. Disintegration is the oldest of old news; everyone knows about breakdown, destruction, entropy. Paint and Henry, just off the highway in downtown Boston are the new news. That still in our day we can witness two tough horses, sinews of steel, stretching their noses toward one another, that is news worth hearing.

Well said. It’s a straightforward trick: take as your subject an animal inextricably linked to human affairs, but portray its existence in nature replete and independent of us, and do it with materials that indicate the human hand. (Plus as you say, “tidy up” scrap materials into beauty.) And do it with consummate skill and sensitivity.

There’s a small Deborah Butterfield sculpture, I think Emi (2016), in the office area of Anglim Gilbert Gallery. I want it more than anything. See you in jail 🙂