Foreword to All This Way for the Short Ride

Poems by Paul Zarzyski; Foreword by Teresa Jordan

I hadn’t known Paul Zarzyski very long when I gave him an inappropriate gift. It was the mid-1980s, and I had become enamored with the music of George Winston. I could listen to his moody piano pieces over and over, almost like a mantra, and I thought I was doing Paul a favor when I gave him a couple of Winston’s albums. The next time I saw him, I asked what he thought. He grumbled something about yuppie Musak, and then he came down to the crux of it. He focused so intensely when he wrote, he said, that when he broke out of that interior world and listened to music, the last thing he wanted was something soothing. He wanted hard rock and blues, something like George Thurogood’s “Bad to the Bone.”

I hadn’t known Paul Zarzyski very long when I gave him an inappropriate gift. It was the mid-1980s, and I had become enamored with the music of George Winston. I could listen to his moody piano pieces over and over, almost like a mantra, and I thought I was doing Paul a favor when I gave him a couple of Winston’s albums. The next time I saw him, I asked what he thought. He grumbled something about yuppie Musak, and then he came down to the crux of it. He focused so intensely when he wrote, he said, that when he broke out of that interior world and listened to music, the last thing he wanted was something soothing. He wanted hard rock and blues, something like George Thurogood’s “Bad to the Bone.”

Bronc riders dream of being “tapped.” In the ultimate ride, every iota of wildness and fire that is horse explodes to be matched, leap by plunge and spark by flare, with the body and soul of the rider. This is the bliss of mortal transcendence, for man becomes horse and horse becomes man, churning sweat and thunder, dust and lightning into beauty. For eight seconds, horse and rider tap into some impossible excellence and know each other better than two minds can. At the core is an almost feminine tenderness. Call it intuition. And afterwards — afterwards — release comes with an unfettered gallop and kick, and a lot of brassy honkeytonking. Bad to the bone.

What would Paul Zarzyski have done if his soul hadn’t been kidnapped by rodeo and stolen by poetry? What metaphor could carry the intensity with which he lives the language better than a bronc? Poems and broncs are crucibles where a lifetime of yearning and passion distill into something pure. Eight seconds or twenty lines: the great rides, like the great poems, take a lifetime to create and are both ephemeral and lasting, shimmering like some eternal afterimage of sacrifice and desire on the edges of consciousness. They strike sparks off the wild soul we each still have within us and make us believe, once again, in the impossible.

A few years ago — not so long after I’d gotten to know Paul — I had the chance to spend several hours interviewing Philippe Petit, the high-wire walker who had come to international attention for his unauthorized walk between the Towers at the World Trade Center in New York. An intense man who had devoted his life to the twin passions of beauty and danger, Petit immediately reminded me of Zarzyski. He told me that in the old days, before cable replaced rope, high-wire walkers worked barefoot and the marks of their trade, invisible so high up in the air, were the parallel lines of callus on the bottom of each foot that became, over years of practice, as hard as horn or bone. These calluses caressed the rope and, when the wirewalker came back to earth, he could feel them between himself and the ground, a constant reminder that he owned the air.

The most deeply lived passions shape us in invisible and not-so-invisible ways. Broncs have rearranged Zarzyski’s anatomy — nothing major, but you can catch it in his walk, especially on a cold day, and his left arm is a few centimeters longer than his right. Bad to the bone, you might say. And poetry? Maybe its mark is that acrobatic tongue, miraculously at ease on a language stretched tight and resonant above a dangerous abyss. Not music exactly. Certainly not George Winston. But something full of dance and devilment. Something good to the soul.

Enter Barbara Van Cleve. Chronologically, she could be Zarzyski’s mother (if she’d started early). Spiritually, she is more like a twin, another ageless prodigy having way too much fun at what she does. Barbara wears the marks of her own passions and experience, a stiff-hipped walk earned by decades of Montana winters a-horseback, and the aches and pains of one who has carried a lot of heavy photographic equipment a good many miles.

Barbara’s father, Spike Van Cleve, was a renowned storyteller, and Barbara can craft a pretty good tale herself. But perhaps it was the art of listening, honed early, that most shaped her visual expression, for hers are images that start with knowing the subject from the inside out. In the West at large and rodeo in particular, any good photographer can catch flash and grandeur. Barbara captures something more, which is authenticity, the deep and lasting story within the transitory moment rendered on film. Hers are strangely verbal photographs, full, in some inexplicable way, with language, which is what makes them pair up so magically, so mystically, with Zarzyski’s poems.

A few years back, the scholar John Briggs introduced me to a twenty-dollar word that has changed forever the way I look at art:”omnivalence.” If ambivalence is a middle-of-the-road, neither/nor proposition, omnivalence is that quality of more that resonates from lasting work. The Mona Lisa has an omnivalent smile, filled with more than we can quite articulate: it is sensuous and virginal, innocent and knowing, cynical and sincere. The first line of Hemingway’s story,”In Another Country” similarly rings with omnivalence: “In the fall the war was always there, but we did not go to it anymore.” Wistful, cynical, relieved, despairing: we can’t get to the bottom of it, and when we can’t fully describe it, we can’t forget it either.

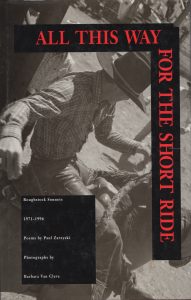

Either Van Cleve’s or Zarzyski’s work, taken alone, has an omnivalent quality. Dovetailed side by side, the effect can be downright electrifying, as in the title poem, “All This Way for the Short Ride,” inspired by the death of Zarzyski’s rodeo compadre, Joe Lear. A poem commemorating death, the images are those of fertility and birth as the bull rider’s pregnant wife comes stunned into the arena to pick up “her husband’s bull rope and hat, bells/clanking to the murmur of crowd/ and siren’s mewl.” The images throughout are fetal and infant: that mewl; the poet, a bronc rider, imagining even as he mourns his friend what he wants for his own upcoming burst from the chute, “details of a classic ride–body curled/fetal to the riggin’…”; the baby inside the wife’s belly fighting “with his mother for air/and hope…,” learning “early/through pain the amnion could not protect him from…. the sheer/peril of living with a passion/that shatters all at once….” The images circle back to the poet’s own passion, to that which simmers like intoxication, aware of possible futures and riding in spite of (and also because of) them, “flesh and destiny up/for grabs, a bride’s bouquet/pitched blind.” The poem leaves us trembling with loss and exhilaration, futility and earned greatness, blind lust and exquisite tenderness. In Van Cleve’s photograph juxtaposed beside the poem, a bronc rider leans so far back as to be almost exploded by the ride, wide open in his vulnerability and also his grace, his position so extreme we aren’t sure if he is purely tapped or already over the edge.

All This Way for the Short Ride cuts to the bone and reaches the marrow of pure meaning: the good of things, the bad of things, the interior world where good and bad can’t begin to describe things. This book is about rodeo. This book is about life. It will last.

©1996 by Museum of New Mexico Press